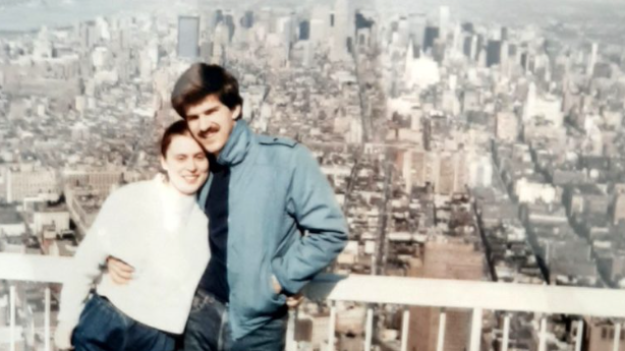

Mieszko: People came to our shop like to a confessional in the church. People would cry, confess their sins, and look into your eyes to see if you’d forgive them. But I’d like to take a flamethrower to that store and destroy it. It was a prison for me. I served a twenty-five-year sentence in that place.

Beata: I loved our store. Customers would come in and tell us their entire life stories. We were needed there. Alcoholics came in who didn’t want to drink anymore, victims of domestic abuse, and grandparents with photos of grandchildren they’d never had a chance to see.

Mieszko: You had a confessional there. Our Lady of the Delicatessen. People would cry, confess their sins, and look into your eyes to see if you’d forgive them. But I’d like to take a flamethrower to that store. It was a prison. I served a twenty-five-year sentence in that place.

Mieszko: We didn’t come to America because of poverty, not at all.

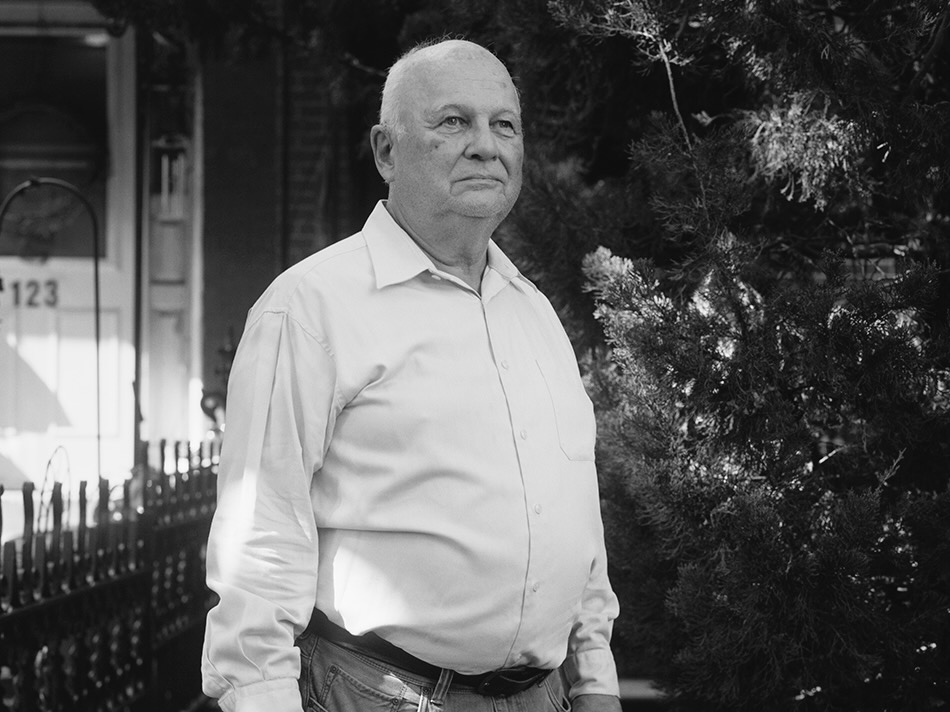

Beata: Only because of a great love that his mother couldn’t accept.

Mieszko: I met Beata during my first year of college in Opole.

Beata: His mother had plans for her eldest son. The most handsome, the smartest. He was going to be the president of Poland, and, in her opinion, I wasn’t fit to be the First Lady. For many years I didn’t fit into her vision of the world.

Mieszko: When I was in my second year of college, my mother asked me, “Son, where are you going to spend your summer vacation this year?” I replied, “Mom, I’m going to do an internship, then I’m camping with Beata.”

Beata: If she’d known what would happen, she would’ve agreed to that camping trip.

Mieszko: Soon afterward, my mom told me, “You know, your grandma misses you. You ought to visit her in America.” I loved my mom, but I knew she only wanted me to go to America, so I wouldn’t go camping with Beata. There was no arguing with my mom, so I had no choice but to agree to visit my grandma in Greenpoint. But I immediately went to see Beata because I’m stubborn, just like my mom.

Beata: He rushed over to see me and said, “Take some time off from your studies. Come and visit me, we’ll stay in America for one year and earn some cash to rent an apartment. Don’t say anything to anyone about it.”

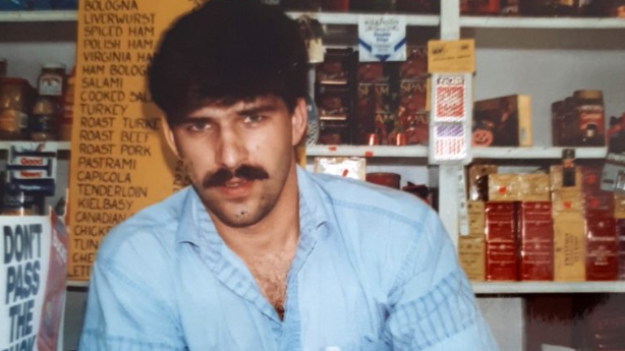

Mieszko: I got an official invitation to the USA from my grandmother. I got a Polish passport and visa to the USA without any trouble because my mother was an important person – she was an active member of the Communist Party. She had connections with people in the Ministry of the Interior. Martial law was coming to an end, and planes from Poland could not land in New York, but thanks to my mother’s connections, she arranged a trip for me to New York via London. My grandma’s friend picked me up from the airport. I arrived at her place on Eagle Street. When I got out of the car, I looked around and thought, “Holy shit, this can’t be true.”

I thought I was from a total backwater, but my legs buckled under me when I arrived on Eagle Street.

Mieszko: The crooked, wooden row houses covered in clapboard siding looked like a slum. The entire neighborhood looked like that. While climbing the stairs, I was afraid they’d collapse under me. I opened the door to my grandma’s apartment, which was dark and had connecting rooms. The kitchen was at the end of a narrow hallway, and in the middle of the kitchen, there was a bathtub. You could enter the rooms from the kitchen. Cockroaches were running everywhere. If I were sitting in that bathtub in the middle of the kitchen when someone stopped by to visit my grandma, I’d fold down the wooden flaps to cover myself.

Beata: He called me, devastated. If I move too fast, I might fly through all the apartments and down the street. It seemed to him that the walls were made of plywood, and he was pretty right about that.

Mieszko: I didn’t know living in such a horrible apartment was possible. I’d never seen anything like it in Poland. Maybe because I’d lived in a former German town. Even our cellar was better than my grandma’s apartment. While I was growing up in Poland, my family had also been quite privileged because my grandma often sent American dollars to us. The conversion rate was terrific – four hundred and fifty złoty for one dollar, and later eighty złoty. We wore clothes that made people’s eyes pop out while my grandma was starving in America. She received a low pension but paid minimal rent, sending nearly all her money to her family back in Poland. I started looking for work.

Beata: I visited Mieszko’s mother in November. I told her Mieszko needed a winter jacket. His mother was shocked. I went to the airport with a coat for Mieszko. After I arrived in America, we installed a frame and curtain over the bathtub.

Mieszko: My grandma took me to her church. Only older people attended the masses. She introduced me to the priest. He heard my voice and said: You’ll read the Bible passages. Beata and I served as readers in the church for years. The old ladies were delighted because they could turn off their hearing aids. I entered the Polish community from the sacristy.

Beata: We didn’t want to stay in America. But Mieszko wasn’t granted an official leave of absence from his studies. His mother hadn’t arranged it for him because she wanted him to return to Poland. But he didn’t return. A year later, he would’ve been sent to the army to do his mandatory military service.

Mieszko: We made a decision – we wanted to be together, so we stayed. Things became a bit easier. We started to feel comfortable in America and thought we could build a life here. We knew dozens of people who constantly figured they’d return to Poland one day, so they treated life in Greenpoint like an extended summer vacation. Some lived like that for thirty years.

Beata: On Sundays, we went to church, where the smell of mothballs mixed with the stench of undigested alcohol. After mass, Mieszko’s grandma introduced us to her friends. We were new to the community, so the older immigrants came to us and asked how things were in Poland. They told us about themselves. I’d never met people in Poland who lived the way they did.

Mieszko: They said they just wanted to earn money for a little while in the USA and then go back to Poland, but they never managed to go back. They had pieces of paper with lists of things they planned to buy. A combine harvester, a tractor, a TV set, and a manure spreader.

They wanted to send two thousand dollars to Poland because their daughter was getting married. When they’d collected the money, they took it out of their socks and sent it to Poland by postal order. Two months later, a man’s wife would send him a photo of the combine harvester – now he could cross it off the list. And start saving up for that.

On Saturday, some drank at home, and others went to the Dom Polski on Driggs Avenue. It was a community center and club for Poles, established after World War I. There was a disco there charging five dollars for entrance and a taproom. The musical repertoire was relatively simple, but from time to time, there were parties where well-known musicians performed. There was also the Continental Club, which opened in the 1980s. We used to go there, too.

Mieszko: Before I arrived, my grandma had arranged for her sister’s son to come to the USA. He managed to legalize his stay – I have no idea how. He got a Social Security number, which is necessary for getting any job. And he was kind enough to lend it to me so I could find a job. Meanwhile, he was working at his position with the same number. It wasn’t a problem for the system if people worked in various places with the same social security number. The more contributions, the better. Of course, it would be best if it was the same person. But it didn’t always happen that way in Greenpoint.

Beata: He took you around town and found your first job, making dolls.

Mieszko: He said he knew someone who needed a guy for a toy factory. Christmas was coming, and a factory two blocks away began hiring doll-makers for the Christmas store displays. The boss, who was gay and Jewish, walked around the factory with his boyfriend, holding hands. This didn’t bother the crew because they were happy with their paychecks. I went and signed up.

The mechanical department manager Jurek led me to the conveyor belt and showed me what to cut and twist. About a dozen or so guys worked there, all older than me. They were hungry for news from Poland. I had a cassette tape with Polish hits on it – they immediately loved me.

Because they were musicians, they’d come to the USA after martial law broke out to play concerts. The American concert booker had told them that martial law was Poland’s internal affair, and the shows still had to go ahead because tickets had been sold. So, they came, they played, and they all stayed.

Next to me at the conveyor belt stood Krzysztof, a saxophonist who’d performed at the Jazz Jamboree. I learned more about music in that factory than I’d learned throughout my entire time in school. They put me next to my friend Fuciek. In the morning, Fuciek would bring a box full of empty dolls, each forty centimeters tall. He’d hand me a doll, and I’d rip off its head and put it on the table. We opened up the doll’s back, and we both picked up a drill because each doll had to have a hole in its right leg and a hole for ventilation. Then, on the circular saw, I’d cut the little hands, and he’d cut the doll’s back so it could ventilate adequately.

We’d insert an electric motor with an arm sticking out, run an electric wire through the right leg, and plug it into a socket. If the doll moved its right hand and head, we put two drops of glue on it to make the head stick—one hundred and forty-four dolls in four hours. Some Puerto Rican ladies dressed the dolls in Christmas outfits in the next room. The next day a new order came: the dolls needed to hold candles. Then we assembled two-meter-high nutcrackers. Later, when my wife and I were walking down Madison Avenue in Manhattan, we saw my dolls waving at me from a window display.

Beata: On weekends, the musicians played at the Polish Home in Greenpoint. After the Continental Club opened, they performed there too. They played at our wedding. Those friendships have lasted a lifetime.

Mieszko: The wife of one of the guys was taking care of a millionaire’s house in Greenwich, Connecticut, while he was away. We drove there, cooked, and drank wine. It was a beautiful neighborhood. There were luxuries in that house we’d never seen before.

Beata: We began to realize we were living in a ghetto and that America was a little bigger than Greenpoint. And that Greenpoint had its separate history.

Beata: Mieszko’s grandma’s friend took me to Williamsburg by bus, to the apartment of a Polish Jew named Regina, who sent Polish women off to Hasidic homes every day. I got off the bus at Bedford Street and panicked because it was more run-down there than in Greenpoint. Many Hispanics, abandoned factories, prostitutes hanging out on street corners, and small groups of men huddling in doorways. I entered a stairwell. Some women were sitting on the stairs on the first floor and speaking in Polish. They told me to wait my turn. A fifty-year-old woman was sitting in a room with a phone in her hand, taking orders. Every so often, she’d come out with an address written on a piece of paper, call out the name of a woman waiting in the stairwell, and send her off to a customer. Regina spoke excellent Polish.

Suddenly she came out, wincing, and said she couldn’t arrange anything else because she had a headache and needed to lie down for half an hour. She asked if one of us could speak English and replace her on the phone. Today I think that if those girls waiting in the stairwell had spoken English, they wouldn’t have been there in the first place. I volunteered, even though my English wasn’t excellent.

She put me behind a desk and told me to answer the phone. If someone called, I was to write down the address. Fortunately, the Jewish woman who hailed from Williamsburg could say a few words in Polish. She came back half an hour later. She said that as a reward, she’d hook me up with a good cleaning job, and her husband would drive me there. She warned me not to mix kosher and non-kosher things in the kitchen, or I’d be fired and wouldn’t get paid. My heart was in my throat. You never heard about any Hasidim in Opole, much less from Williamsburg.

Beata: There was an American Jewish woman, a journalist, living in an elegant penthouse on 33rd Street with a cat. She worked for the Daily News. She smiled and said I should do some “laundry,” – but I stared at her because I had no idea what that word meant. After fifteen minutes of trying to explain it to me through hand gestures, she finally dialed a number and handed me the receiver. On the other end was a Polish woman named Ula, also a cleaning lady. She probably cleaned for that lady’s friends. She had a much better understanding of English. She was nice. She explained that the lady would give me some coins, and then I was supposed to go down to the laundry room in the basement of the building and put the cash and the dirty laundry into the washing machine and then into the dryer.

That’s how I learned what “laundry” meant. I was relieved. At the end of our conversation, Ula asked me to call her sometime to chat. It turned out we were neighbors. She was much older than me, in her forties, but quite vivacious. She decided she needed to take me from Williamsburg to clean in Americans’ houses, which were quite sterile because Americans didn’t cook at home and only smoked when they were in bed.

Mieszko: It was Ula who sent you to Beata and Władek’s place. They lived on the corner of 72nd Street and Third Avenue. He was a Polish Jew. They’d left Poland after the political unrest in 1968. Władek was the superintendent of an entire Manhattan Upper East Side building, with doorkeepers and elevator operators. As part of his full-time job, he was allowed to live in one of the apartments. His wife sold greeting cards on the Lower East Side, where Polish-speaking Jews ran stores. Poles from Greenpoint would buy curtains and faux fur there to send to their families in Poland. We became friends.

Beata: I asked Władek if he had any work for my husband. He was the boss of twenty-eight handymen who roamed around the building, doing odd jobs. He did, but Mieszko would need a goddamn Social Security number.

Mieszko: I finally had to buy one for myself in Greenpoint.

Beata: Everyone was buying them at the time.