The problem was with the floors because the lady showed me that I should wash them on my knees. How is it on my knees? I wanted to know if she wanted me to kneel before her. But she gave me an old towel and showed me: put it under your knees and wash the floor. That’s how I washed dishes even at home in Poland. My husband was surprised. “What is this new custom?” he asked. “Jewish,” I replied.

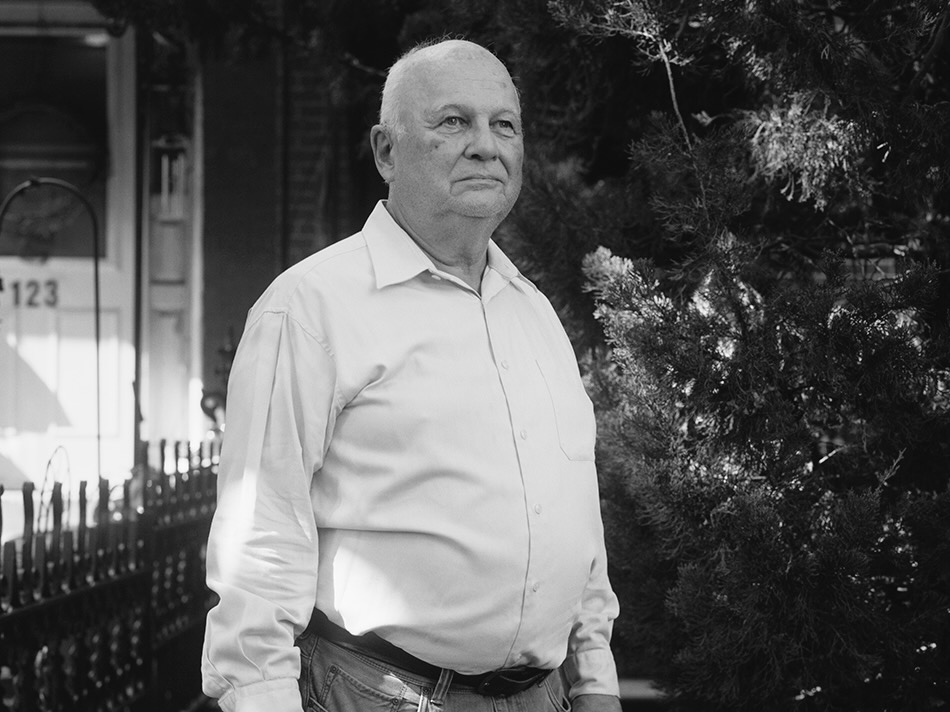

In 1993, I came to Greenpoint for the first time. In the beginning, I rented a room. Ten people lived in one house. We had a shared kitchen and one bathroom for every five people down the hall. Everyone was supposed to clean up after themselves, but it still needed to be cleaned. I mostly bathed in flip-flops so as not to get a fungus. I had a table in my room and a microwave on it. Pots and pans were stored under the bed, and the communal kitchen was cluttered.

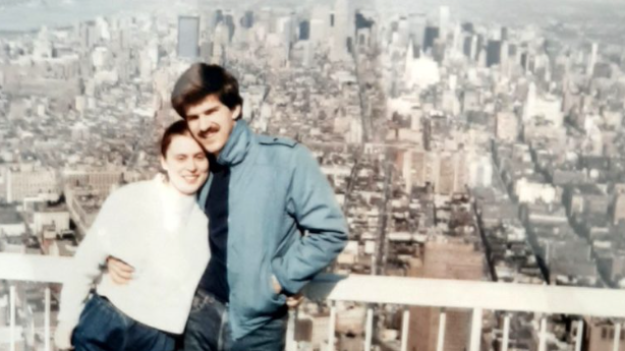

A chest of drawers and a TV were in the recess in the wall. I kept glasses in the chest of drawers because when a friend came over, I took a beer out of the fridge. From time to time, my son came to visit from Poland. Then I slept on a mattress on the floor so that the boy could get some sleep. My son and I had an adventure once: we went to Manhattan. I said: “Here is an opportunity; let’s eat out.” We took skewers from the kind of food truck. It did us some harm. My son then joked that they were made from dog meat. Who knows, you are not able to check.

In 1993, we drew a Green Card. I didn’t even know that my husband was planning this emigration. He had access to a typewriter in the Polish city of Ostrołęka and filled out a form. They printed these forms in our local weekly. One day he comes and says: “Basia, we will earn money in America.” Did I want to leave permanently? I don’t know.

First, I went to the US on a tourist visa; my friend got me an apartment. He said I could clean “plays,” or apartments in Williamsburg, for Jews.

But how was I supposed to find this Regina since I didn’t know the language of Williamsburg, and I was outside of Poland for the first time?

I’m tough, and I knew I had to deal with it. A friend told me, “286 Cooper Street,” and I got there. There were already many other women from Poland in Regina’s apartment. I was the fourth or fifth in line. When I walked in, Regina asked if I spoke English. I said no, and that, for the first time, I would need something not too difficult to clean.

Regina gave me a piece of paper with the address. On the way, I asked passers-by for directions, using sign language: where should I turn? Right or left? I didn’t know what “block” meant, but I figured it out from the context. If someone said “block” and showed three fingers, I understood that I must turn in three blocks. I didn’t have time to go to school to learn English; I picked up the language on the street.

Finally, I knocked on the door. A woman opened it and said, “Change the dress,” and gave me a hanger. That’s how I knew I had to change clothes. Then I wrote on paper which liquids are used for what. I heard my friends had a problem with it. One was cleaning leather furniture with Windex.

The problem was with the floors because the lady showed me that I should wash them on my knees. How is it on my knees? I wanted to know if she wanted me to kneel before her. But she gave me an old towel and showed me: put it under your knees and wash the floor. That’s how I washed dishes even at home in Poland. My husband was surprised. “What is this new custom?” he asked. “Jewish,” I replied.

The lady was surprised I did not wipe the dust with a glove or a broom. And I liked to check with my bare hand whether there was dust or not. I did so because I liked how clean it was.

The lady was very pleased with me and hired me permanently. She said I was smart.

God, I was pleased with myself – the first day at work and such a success.

I spent my first Christmas in New York with Stenia and other tenants: I made dumplings and cabbage soup and set the table. Stenia bought a present for me from Jews in Brooklyn. Someone from the first floor dressed up as Santa Claus. Santa Claus. I laughed because we were not children. I felt right at home.

When we decided to leave Poland, we could go to New Britain, where my cousin was, or Greenpoint. I told my husband, “Let’s go to Greenpoint: here are subways, here is life, no need for a car.” My husband joined me, and the children stayed with their grandparents in Poland. They didn’t listen to their grandparents. They were disobedient. My parents complained about them to us over the phone. We explained that the children pretended not to hear them. I told my mother, “If they don’t listen to you, hit them with a belt.” We didn’t want them to come here; it was better for them to stay home. In Greenpoint, the houses were ugly, like grain warehouses full of cockroaches and bugs, which went from apartment to apartment. It was awful.

My husband did not like it here. After a few years, he returned to Poland. We saw each other because I came to Poland every few months. And then I went back to Greenpoint.

Did our long-distance marriage survive? It survived. My husband is from a good family; I knew who I was marrying. And if he wants to sleep with others, I let him sleep around. I would not put a counter on him, just so I didn’t find out, and then I didn’t get sick.

I liked other men too. I want to look at a nice body on the street. At young boys and elegant young girls too. And sometimes I think that I still wish I had that youth. It’s a pity that it is what it is.

Someone said: “Basia, how have you changed? You used to be so slim.” My answer is short: now I have an appetite, especially at night. I console myself with the thought that I have younger friends who look much worse. But I don’t tell them anything, only compliments.

Once, I became friends with a professor. I worked for other Jews in Manhattan and cleaned during Passover. It was getting dark, and I was afraid to go out on the street. You know how it is in Manhattan. The Jewish woman told me to stay with her for the night. I called my friends, who were waiting for me in Greenpoint. “Klementyna, I don’t know how I will return home today. The Jewish woman says to spend the night with them.”

“Where are you, Basia? I will pick you up.”

“I don’t know where I am, somewhere in Manhattan. I don’t know anything else.”

“Basia, give the Jewish woman the phone.”

And I heard him talking to the Jewish woman in English. She gave him the address, and Stanisław came for me. We started to converse. Stanisław was a man of culture, but his wife had cheated on him. He wanted to talk to me about it.

Later, my husband called me from Poland and said, “Basiu, don’t fall in love with him!”

We still have contact with Stanisław to this day; he lives with his student now.

I was offered another job – to care for older people, but I didn’t decide on a change. I prefer cleaning. Care burns the eyes, so people say.

When friends in Poland ask me what I do, I say I have a business. But what kind of business – I do not say. What for?

The same in Greenpoint. I don’t tell anyone what I do in Poland or how much I earn. I won’t say where I live. I advise everyone not to tell anyone.

My friend told her dentist that she was wealthy. And he has been doing her teeth for three years, with no end in sight. He constantly comes up with new problems, and you must pay for them.

You have to be careful not to be deceived by friends and strangers.

My only regret is that I didn’t buy a house like everyone else. For $80,000, you could buy one, and the lodgers would pay it back. I did not think it through.

But I do not complain. America is good if you are either very rich or very poor. So I have everything: I had my teeth done, eye surgery, and I’m going to treat my knee – everything right away and for free.