I don’t know how it is now, but burglaries were the order of the day back then. When you walked down Manhattan Avenue at night, it looked like a metal canyon; all businesses were covered with armored roller blinds. Plus one all-night deli, where three people were murdered later, and only a hundred dollars were stolen.

I was twenty years old and left for musical reasons – I wanted to visit famous jazz clubs and go to concerts. I wasn’t interested in money; I didn’t think about saving dollars.

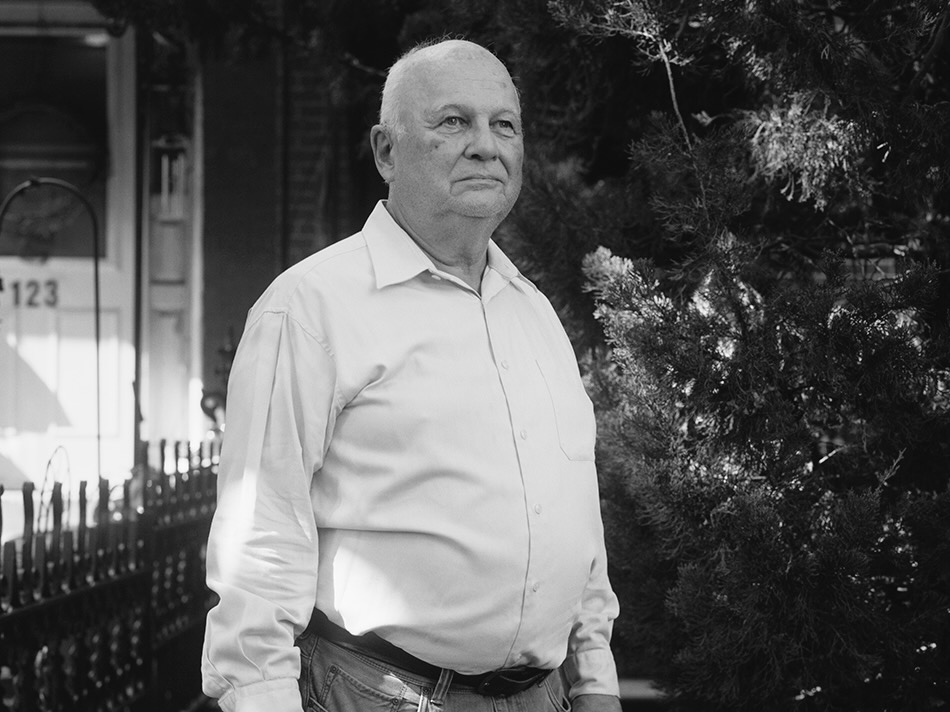

It was September 1981, and I came to the States with my girlfriend. Our American adventure was supposed to last only a few months. I spoke English but did not know the American realities. I left Poland with a Grundig tape recorder and a set of cassettes, without which – as it seemed to me before leaving – I could not live even in the USA. These were Marek Grechuta’s recorded albums. As you know, in the USA, the current has a different voltage, so my Grundig did not work.

We came on the Batory ship, and there I found out that there was a neighborhood like Greenpoint. I’ve never heard of it before. My father gave me a hundred dollars for the trip, so I thought that at the beginning, we would rent a room in a nice Polish hotel.

From Montreal, we took a bus to Manhattan’s Port Authority station and passed 42nd Street, which I recognized from the movie Taxi Driver. From there, we took a taxi to Greenpoint without any problems. Our driver must have had a lot of fun when he heard we were looking for a hotel in Greenpoint. In the evening, he dropped us off at the corner of Manhattan and Nassau streets with Grundig, suitcases, and a guitar.

Of course, there is no hotel there, in 1981 it was even less so. Polish passersby took us in. It was only in December 1999 that the owner of the apartment, also a Pole, realized that twice as many people lived in the apartment as he thought and threw us adrift just before Christmas.

When I saw that my tape recorder was not working on American electricity, I used my last money to buy batteries for a giant Electronic Store on the corner of Manhattan Avenue and Calyer. I came across Poles, who wanted to buy a radio tape recorder but could not communicate in English with the owner. I helped them, advised them, though I had no idea what I was talking about, and left with the batteries.

The owner ran after me. “Where are you working?” “Nowhere. I just arrived. “Would you like to be here?“. So I got the job immediately before I even started looking for it. I tore into Manhattan and walked its streets from morning to night.

It was hard to get a job back then. The years of “Solidarity” brought the invasion of Poles to the United States, and whoever landed in New York inevitably ended up in Greenpoint. I knew nothing about electronics, but I could read the manual, and that was enough.

The shop where I worked was owned by Sephardic Jews born in Brooklyn. After a while, they had three stores on Manhattan Avenue, but they weren’t brilliant but highly greedy. They only thought about how to get rich as soon as possible. This caused a lot of trouble. They talked about money all the time, and only about money, which for me, a student from Warsaw, was shocking because money was never discussed at home; moreover, it was perceived as a lack of culture.

The owners had such an attitude toward customers that they wanted to cheat everyone. Poles, of course, too. But there was nothing discriminatory about it – they enjoyed fooling everyone equally.

It quickly turned out that I have the qualities of a good salesman. It’s mainly because of good contact with people; knowledge of the product has little to do with it. My boss told me that a good salesman sells TVs one day and tires the next; the merchandise doesn’t matter. Soon the boss trusted me enough that I started attending their family barbecues in New Jersey. And I was the only one who knew the code for the alarm at the store door so that his family, including his sons, would not rob each other.

The boss knew they were dimwits and loved to show off and play mafia. We had more than one break-in there. Once a thief broke through the ceiling from the floor of the dentist, Dr. Weissberg. I came to work in the morning, and everyone was already waiting for me: the police, the dentist, and the boss’s sons. And I, who was illegal, opened the store door for them. The dentist immediately told the police officers that I was from Poland and had the keys, casting suspicion on me. Even my boss laughed at him.

I don’t know how it is now, but burglaries were the order of the day back then. When you walked down Manhattan Avenue at night, it looked like a metal canyon; all businesses were covered with armored roller blinds. Plus one all-night deli, where three people were murdered later, and only a hundred dollars were stolen. No one wanted to work the night shift there after that until my current friend from Poland was hired. He concluded that the likelihood of a repeat murder in the same place was low. And the perpetrators there were never apprehended.

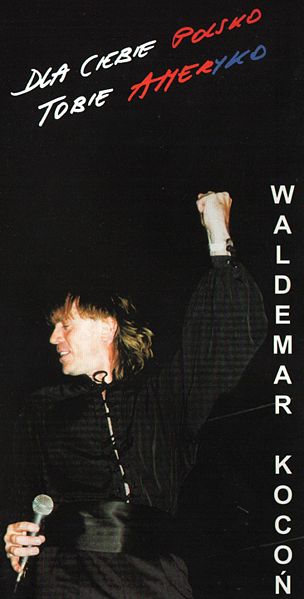

Working in an attractive store gave me invaluable insight into the environment of Poles, cut off from the country by martial law. People roamed the streets and talked about themselves. It was a closed group because no one was leaving or coming. Every new person could be distinguished from a kilometer away: a new Pole! Is it sometimes not “ubek” (agent of the communist secret service)? If a Pole was walking down the street in the early afternoon, he was already suspicious because he should be at work. People were paranoid but quite justified.

I met compatriots; I didn’t know that they existed before. Homeowners, so-called “the old Polonia.” The tenants of these houses were economic emigrants from Poland, class B, C, and D. They were primarily middle-aged people, almost all men; women as expatriates were rare at the time. Some of them had never even set foot in Manhattan. They told unbelievable stories about Americans running naked or shooting each other in broad daylight.

The emigrants saved money on everything. For shopping, they would go to Key Food on McGuinness Boulevard and buy huge trays of chicken wings, sometimes four dozen at a time, on which they would then cook broth for the week. Sometimes they bought wine vinegar, thinking it was cheap wine – I saw it with my own eyes.

There I only met a few people to talk to. I redirected all activity to Manhattan, where real life then: movie theaters, concerts, record stores, bookstores, and restaurants with world cuisine, which I knew little about. In Greenpoint lived an exciting man called Bison, a well-known hippie, a dissolute dude with a beard to his waist. I later learned that he died as a homeless alcoholic in Tompkins Square Park in Alphabet City – a Manhattan neighborhood, in the eastern part of the East Village, between A, B, C, and D avenues. That is where the action of “Antigone in New York” takes place.

When martial law began, on a patriotic wave, I started going to the club of the organization “Pomost,” which was located nearby on Manhattan Avenue. It was where Bizon was active. They organized concerts and lectures. In 1982, Jacek Kaczmarski performed there. It was a kind of Polish self-defense, militant mood: communists threaten us, Puerto Ricans threaten us, some utter bullshit without sense.

In December 1981, they started saying that “we must unite.” They were talking and chugging vodka. And the next day, everyone went to work—typical Polish straw enthusiasm. And everything ended up with nothing.

Did Puerto Ricans threaten us? Yes, a little. Poles were afraid of them because robbery attacks happened. Most often in the metro area on payday. And Poles didn’t form gangs or walk around with guns. I remember once a Hispanic hoodlum, a slick dude, walked into a store, looked at the radio, and said: “Let me rob a couple of Polacks, and I’ll be back.” He winked and left. He didn’t come back.

I had no problem with the Puerto Ricans; we knew each other by sight and from the store. Once, they were buying a big radio from me, and I was tying a box to them with string, and since I didn’t have scissors on hand, I said: “Get a knife, muchachos.” “We don’t have one.” “What, you don’t have a knife? Then what kind of Puerto Ricans are you? “. They bought big battery-operated ghetto blasters. They would roam around the neighborhood with them and play them at total volume, and after an hour, they would come back complaining that the batteries had run out. There was a joke about them: How many people does it take to bury a Puerto Rican? Ten. Four to carry the coffin, and six to have the radio.

Close to ‘Pomost’ Club, there was a famous mattress store for Poles, who began arriving in Greenpoint in waves in the late 1980s. These mattresses were collected from dumpsters, quickly refurbished, and stuffed. Luis, a Colombian, owned the store; his employee was Juan, called by Poles Jaś. We taught him to ask customers in Polish: “Is this mattress guaranteed or pissed? “.

My job was light compared to the hard work of construction sites. Until 5 PM, we stood in the store, almost idle. We watched videos; I read The New York Times, which my boss subscribed to but didn’t read. After five o’clock in the afternoon, the traffic in the store started, as people were returning from work. I had no problem working on Sundays, not for religious reasons; I only regretted not having weekends off.

There were always crowds on Sunday. We were hit by a wave of people coming out of the churches: from Stanisław Kostka church or Cyril and Methodius. People came mostly to chat between the central mass and the pork chop, with whole families and groups. Most of these people just bothered us and didn’t buy anything.

For many, Sunday was the only possible time because they worked six days a week. For most compatriots, it was also the only entertainment available.

Poles mainly bought calculators with trigonometric functions for children in the country. They were also required to purchase two-cassette “stereos” for the family. It had to be 110-220 type equipment, a multisystem that was more expensive than the American sets, which pissed off buyers. It is worth recalling that the NTSC color system (majestically called “Never The Same Color”) existed in the States. In Europe, it was PAL, with an additional complication in the form of SECAM, adopted in Poland from France. This made it difficult to buy equipment for the country, and all multisystem and 110-220 volt goods belonged to the “gray zone” – these devices did not have an American warranty.

Price-wise, we were not able to compete with stores in Manhattan. Customers learned quickly. “It’s too expensive! So I’ll go to the Jew on Delancey!” – they threatened us. Only that Jew was in Manhattan, where not everyone wanted to go. The breakthrough came with the VHS tape camcorder, a real hit in the mid-1980s. At first, I didn’t know what was happening because everyone was asking about these cameras. My colleagues and I asked, “What the fuck are you doing with the camera, man? “. Customers replied, “Now there’s no life without a camera!” Then they would record themselves with these VHS cameras on the streets of Greenpoint and send stories to their families about the beautiful life in America.

Over time, tapes from Poland began to arrive: on them, for example, a shiny Toyota bought with dollars sent from the States against a barn and a backyard covered in mud. When compact disc players appeared, it again whetted the appetites of compatriots left in the country. Families from Poland asked for the latest mini stereos, with a CD and two cassettes.

I tried to help our guys not to buy bullshit, and I explained to the boss that this was not a highway store. That these people will not go away because they live next door. And they can’t be ripped off because they won’t buy anything from us again. The goods and fashions changed, and only customers invariably came to see what was new. “Oh, I’ll buy that when I get back to Poland. And this too, and also that” – over and over again. They kept talking about returning to Poland. It was frustrating for the salespeople because the boss asked, “Why do the same people keep coming in and not buying anything?”. “They say they will buy it when they return to Poland,” I replied. “And when will they return?”. Well, in the end, they never came back.

From time to time, tours arrived from Jacków, what we called the Polish district in Chicago. I recognized these people from a distance: they were wealthier, fatter, and wore leather coats and cowboy hats – following Pole’s dream about Texas…

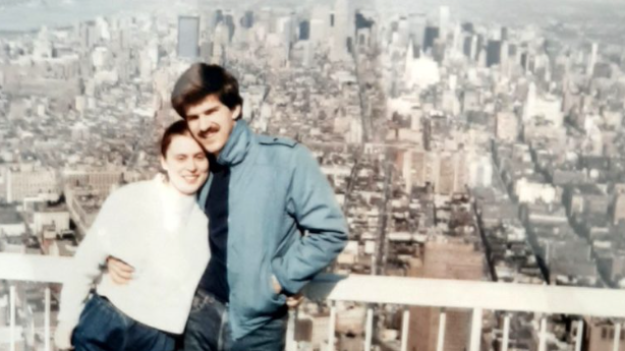

We also had famous clients, such as Waldemar Kocoń and Jerzy Połomski. I didn’t know how to explain to the boss that they were big stars in Poland because they didn’t stand out with their appearance. He suspected I was making a fool of him because famous American singers would never set foot in Greenpoint or even Brooklyn.

My girlfriend and I settled centrally above the Polka Travel office on Manhattan Avenue. We didn’t save much money. I went to the movies and concerts; I saw all the great singers live, except John Lennon, because I didn’t manage to. On the first anniversary of his murder, I was outside the apartment building where he had lived in Manhattan; crowds had gathered there.

In the morning before work, I checked on my artificial fireplace what I had tickets for that day, whether there was a concert or something. When there was nothing, I thought: “Cool, today I will rest.” I went to clubs in Greenwich Village, Madison Square Garden, Carnegie Hall, the Beacon Theater – everywhere.

I fell in love with Manhattan. I found my places there, like Caffe Reggio on MacDougal Street, where I have been going on and off for forty years. Records are my passion; I knew all the stores, those big ones, and collectors’ stores with bootlegs of Dylan for a lot of money. There I could talk to people with whom I had something.

In common, but apart from music, it was hard to find a topic to talk about with them: They considered an intellectual someone who got through “Crime and Punishment,” which is mandatory to be read in high school in Poland. They usually had no idea about history or geography. This ignorance was a new experience for me. “Not my business” attitude.

During martial law, I sent packages to my friends in Poland with coffee, shoes, and jeans. I always stuffed these things with pages of “Nowy Dziennik” with political commentaries, as in Poland, they had no access to reliable information.

Parcels were sent through special “agencies” that had a bad reputation. In my opinion, they were run by ubeks – the secret police. In the 1980s, the communist secret service agents traveled wherever they wanted, in every direction, unlike the rest of the Poles. They lived well in Poland at that time – they had a desk in an office in Greenpoint and a villa in Warsaw’s Mokotow district.

My girlfriend and I lived an everyday life on a limited budget: concerts and restaurant trips to Florida. We had a chance for asylum and American citizenship because, in our homeland, there were tanks on the streets. Only we didn’t plan to emigrate. We wanted to come back and finish our studies in Poland.

So we lived in a state of tiresome ambivalence, aware that we were wasting time, although our friends in Poland were wasting it then, too, and in incomparably less pleasant circumstances. So we lived in a state of tiresome ambivalence, aware that we were wasting time, although our friends in Poland were wasting it at that time, too, and in incomparably less pleasant circumstances.

This first youthful stay in New York gave me a lot – an orientation in popular culture, a broad knowledge of music and film, and an entirely different perspective. We waited until things calmed down in the country and returned to Poland in September 1984.

After returning to Poland – apart from all the culture shock, of course – one thing struck me most. All of our friends and family have been telling us about December 13th. Where martial law found them, what they were doing then, and where they were. Three years had passed, and it was still an unresolved trauma. And nobody asked us about America. For them, it was another planet then.