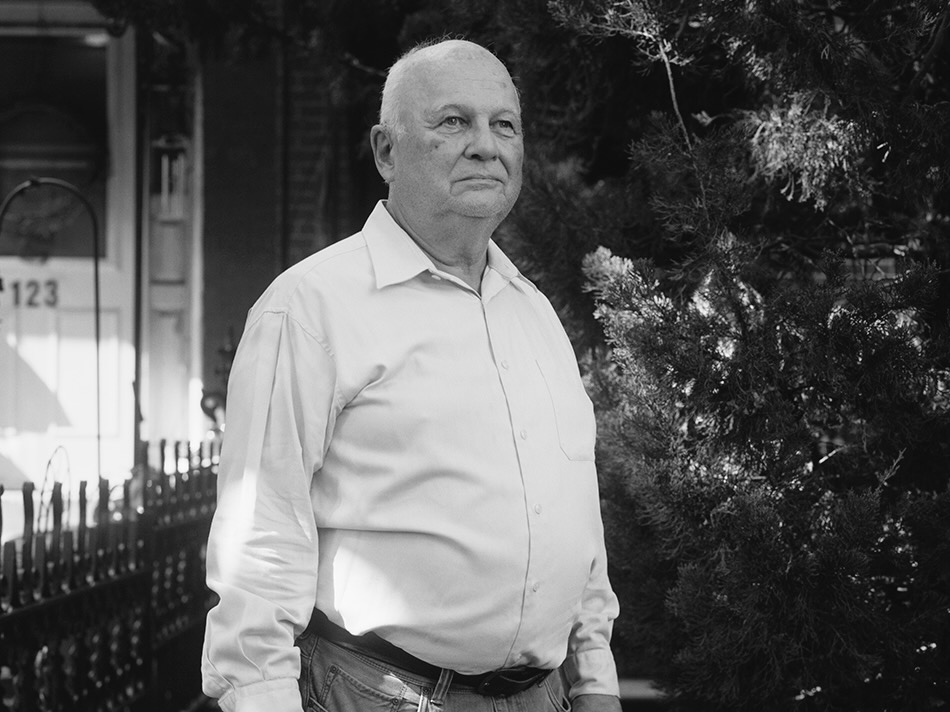

I was supposed to become a sculptor because I graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow with honors. I carved a bust of Ignacy Paderewski, and my professors liked it. I was filled with energy, drawn to the free world, and dreamed about it. In my region in Poland, everyone had someone in America. I also dreamed about making money and earning some dollars.

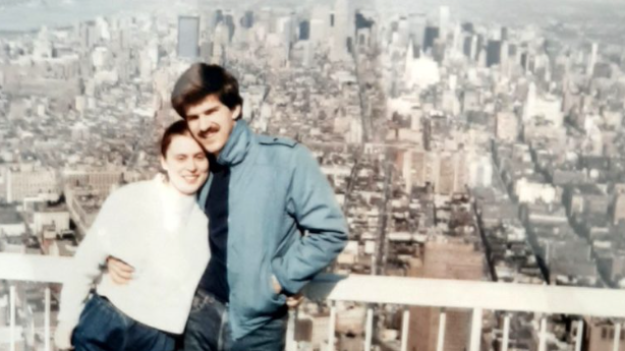

I went on vacation to the Polish district of Greenpoint in 1976. America overwhelmed me because I couldn’t get into the subway. I had to learn how to buy a ticket, get through the gate, where to get on, and where to get off. It’s not easy in Brooklyn or Queens. When you first get on the subway on Jay Street, there’s no way you can go there where you want, especially if you don’t speak English.

I slept with ten guys in a three-room apartment on Nassau Street with Poles and Ukrainians. We stank because we had one bathroom and only cold water, but no one complained. We bought vodka and sausage for the evening. Everyone talked about work, where you could earn some extra money, and who put a beating on the African Americans or Puerto Ricans.

I learned that when you sleep in an apartment with connecting rooms, the most important thing is to choose a room with a window, as police and immigration raids on flats at night. Several colleagues were deported to the country.

It was snowing in January, 4.30 AM; I heard footsteps in the corridor, then pounding on the door. I got up, leaned out the window, and saw four police cars and police officers with truncheons. I jumped out the window and made my way to the fire escapes when the police officers started to break down the door. The boys came out one by one, but Ivan, a boy from Ukraine, jumped right behind me. The boy was too fat and blocked the hole. There were eight more boys behind him, and they tried to push him away; they all cursed at Vasya. I went back up those stairs to help get Vasya out. We all managed to escape then.

Soon after, I walked into a Manhattan Avenue bar to drink. I saw the guys, one with the other, arm wrestling. I came to them because I was relatively strong and eager to brawl. And in a moment, I met Ivan from Yugoslavia. He was a foreman at construction sites; he drove an excavator with a bucket. In the morning, he told me to come to him the next day so that he would help me, so I could also destroy houses for seventeen dollars an hour. Everything illegally.

How are houses torn down? I got up before five and spent an hour on the subway. I took out a sketchbook and drew people of different races: black and yellow; you hadn’t seen such people too often before, neither in Kraków nor in my hometown of Ulanów. A few years later, I arranged an entire exhibition of these sketches.

There were sixteen black workers at the construction site; I was the only white. First, the roof was removed, then the beams on which all the floors were hung. So you finally stood on the edge of the wall on the seventh floor and could see a bare basement. It was covered with rubble from the walls.

We once worked in a tenement house when there was a fire, and the structure was weakened. We knew nothing about it. Somewhere on the fourth floor, we stood on the burned beams – they collapsed under us.

All ten of us flew down. I got stuck on the third floor, hooking on the sewage pipes, and it saved me. But three of my colleagues did not survive.

I couldn’t even check because the police and guards had arrived. It was hell. And I, illegal, had to run away. I was injured, with broken ribs. I didn’t return to my Greenpoint apartment because I was afraid they would pick me up. I went to sleep in the park—right to the next stage of life in America.

To read more about Andrzej, go to: Andrzej Pitynski – Wikipedia

Source: Facebook/PomnikWolynskiJeleniaGora

Source: Facebook/AndrzejPitynski